Composing a Place for Music

“Every day the music center starts at least one conversation between an accomplished student of music and an inexpert passerby.”

The Hotchkiss School in Lakeville, CT asked us to design a new music center that would help bridge the divide between the confident and accomplished performers of music, who were few in number at the School, and the passive, intimidated, uninitiated, and sometimes disinterested, who were many. A new building, it was thought, could transform their moribund music program from a clandestine club holed up in the basement of the chapel, to a vigorous hub of inspiration for all.

We faced other assignments from the School as well: Could we solve the much discussed architectural discord between the gracefully detailed, beautifully proportioned, and passionately beloved Georgian architecture of the original campus (designed circa 1900-1930 by such renowned practitioners as Delano & Aldrich, Henry Waterbury, and Rossiter & Wright) and the modern Main Building, inserted, some feel insensitively, in the 1970s, but to which, nevertheless, we were being asked to connect? This was a challenge that had a less than certain chance of success.

Last, could our building play a part in the Campus Plan’s goal to recapture its once iconic overview of Lake Wononskopomuc, bucolically framed by three hills including Ore Hill, which famously supplied raw materials for the Hotchkiss family’s munitions business at the end of the nineteenth century and which once lent the School a memorable sense of place? The view had long ago been obscured by maturing trees and was now lost entirely, even to the collective memory of the School’s current population. With a program of selective tree cutting, this seemed to us both architecturally achievable and happily in synch with music making.

We, of course, confidently said yes to all, and then, with even more confidence, turned to some old friends for guidance: glass conservatories with their timeless, Georgian pedigree; Boston’s Symphony Hall with its multi-functional flat floor; Hans Scharoun’s Berlin Philharmonic Hall with its intimate seating in-the-round; old-fashioned peeping-type Russian Easter eggs that surprised us with their dreamy, sparkling insides; the petite Sainte-Chapelle in Paris with its ability to transform our spirits despite its small size; accordions and lyres with their resonating shapes; musical notes written on paper that visually convey rhythm and dynamics; and Tanglewood, the summer home of the Boston Symphony with its beloved outdoor venues for music festivals. Surely, we felt, we could do it all with the stuff of these steadfast veterans for counsel.

Making the exterior walls mostly of glass answered many of our challenges. Their transparency would open up outbound views to the Lake and hills while allowing many inbound views through “a window into the world of music” for those not already tenured or otherwise inclined to join in, but who were passing by. A gentle sweep given to the plan would further thrust the transparent building into prominent view from other parts of the campus.

Glass also set the stage on which Mother Nature could perform, which we knew she would do well. The wind, trees, birds, clouds, sun, snow, rain, moon, flowers, and stars would all become Muses for the musicians inside, as if these Muses were the ones performing. This gave the building a communal feel and a relaxed sense of welcome which lured everyone inside to share in its delights. Everyone, it was hoped, would feel that they belonged not only in this place but to this place.

Many of the professional musicians who performed here have also thrilled to this “natural” setting. During one memorable occasion, a noted guest ensemble was inspired to interrupt their performance and invite the audience to turn around in their seats so they too could enjoy the glorious sunset unfolding outside.

Glass, considered by many to have a fully modern disposition, also enabled us to mediate between the modern Main Building and the Delano & Aldrich campus by recalling familiar Georgian conservatories, at least emotionally if not academically. Glass gave us license to be new within the old.

And glass, we learned, has great acoustic benefits. If made thick (we used a half inch thick inner layer of acoustic glass with a one inch airspace and a thinner outer layer of window glass) it has mass and is highly reflective and, thereby produces a clear, crisp sound well delineated and nuanced. Elsewhere, we added sound absorptive curtains to allow adjustment of the acoustics depending on the type of instruments being played and the number of performers.

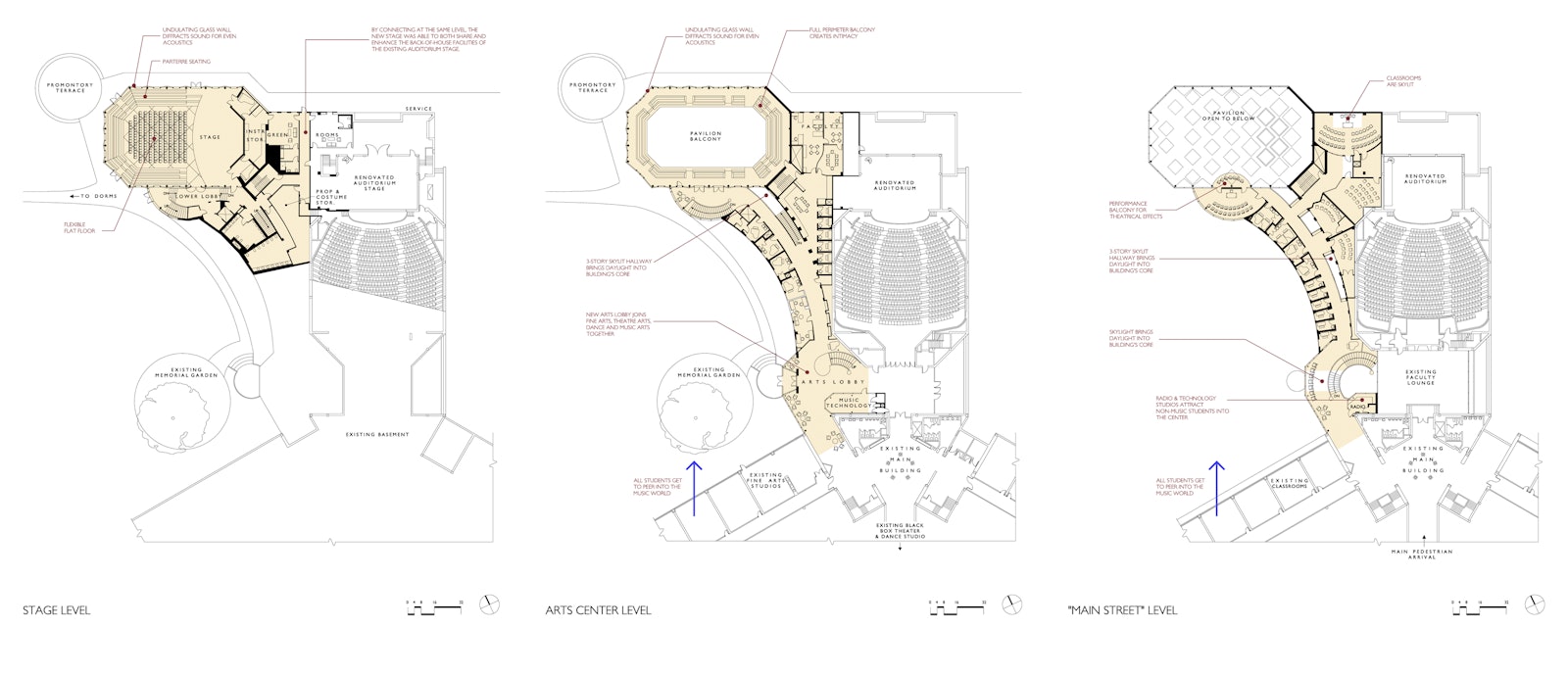

The School’s original request was to simply add some new music practice rooms, classrooms, and a rehearsal studio to its existing drama theater, Walker Auditorium, which, it was assumed, could be used for all musical performances as well as for theater. The School’s thinking was that all it needed in order to transform its struggling music program were straightforward, functional practice facilities. We explored this direction, but soon determined that the extensive cost to transform Walker into a dual-use venue, suitable for both drama and music, would be better invested in a separate concert hall that could also provide a truly inspirational rehearsal hall. It would be like singing in the shower, we noted, where everyone sounds great.

Also, if designed along the lines of Boston’s flat floored Symphony Hall, the new music pavilion, as we came to call it, could also accommodate many other School activities in need of a large open space. This seemed to make good economic sense to all.

The music pavilion is an elongated octagon in plan, configured in the round with floor, parterre, and balcony seating so that it has an uncommon intimacy, whether for a handful of aficionados or the entire school with more than 700 in attendance. Slatted railings at the parterre level and the balconies were carved out of mahogany to evoke the curving bodies of string instruments while their acoustic “transparency” softens and modulates the acoustics.

The two lower panels of glass walls are folded accordion style to diffract sound and prevent any “flutter” between the pavilion’s parallel walls at the ear level of the audience. This fancy step produced a clear, full tone at every seat as well as a playful allusion to a musical instrument.

The School’s radio station, WKIS, and its very hip Musical Instrument Digital Interface Lab (MIDI) were strategically placed at the entrance to the center directly off the corridor of the Main Building. We did this to lure the musically disinclined in for a taste.

Ultimately, we wanted this new Center to tell an alluring story about music that could be understood and valued by anyone. We believed that by imbuing our inanimate building with qualities of life, students would warm to it and begin to see music as an organic part of their humanity.

We took a number of architectural steps to bring the building to “life.” As mentioned, we used the glass walls to ornament the interior with Nature herself. Then we folded the walls to animate the exterior of the building not only with a physical rhythm, but also with the play of light that the facets reflect. The glass, of course, allows the human activity within to enliven the building both day and night from without.

The building’s large volume fills the pavilion with reverberant sound, as palpable as our own vibrating human voice box powered by inhaling and exhaling. The building was meant to seem to swell.

The natural and renewable materials of copper and wood, protected from rain by a broad roof overhang, were designed to age well and personify the building as being stalwart, weathered, and wise.

Doors allow music to spill outside in good weather

The gentle curve of the exterior wall as it connects to the Main Building echoes the grace of our body perhaps in dance or the nape of our outstretched neck perhaps in an affectionate embrace. We believe people feel this connection between the built world and their own bodies empathetically, even if subconsciously.

Doors at the Pavilion’s parterre seating level enable the life inside to spill out onto a festive terrace with the same balmy, communal remembrances as those experienced at Tanglewood, Boston Symphony Orchestra’s summer home in the Berkshire Mountains of western Massachusetts.

The interior spaces contract and expand, twist and turn, rise and fall to tap the emotion of anticipation, in the same way as the dynamics of a musical symphony.

The hallway columns with their rounded capitals are arranged like the written notes on a musical staff and play in concert with the sunlight from a central skylight to give the building a sense of movement and rhythm and jazz.

All in all, we sought to engage people’s whole bodies so that they would feel the significance of where they are. Here, music is experienced by all of our senses in full realization of our whole humanness. From the moment you enter the building, it tells a story about music. It is a story that is ageless. It is not some esoteric essay reserved only for those in the know, but rather, it is a simple story about music and our relation to it that can be heard, sensed, understood, remembered, and treasured by all.

Photos by Trey Ratcliff, Gene Han, World-3, and Peter Aaron/Esto

We're using cookies to deliver you the best user experience. Learn More