A Farewell to Church House and Amistad Chapel

I was saddened to learn of the soon-to-be loss of Church House and its Amistad Chapel that we designed 25 years ago for the national headquarters of the United Church of Christ (UCC) in Cleveland, Ohio. It is not only one of my proudest architectural achievements but also, I am just recently hearing, a powerful and uplifting sacred space for people around the world who came there to worship.

On March 13, Amistad Chapel hosted its last worship service. It was held as the UCC bid farewell to the historic 700 Prospect Avenue building it bought in 1989 from the Ohio Bell Telephone Company, and to Amistad Chapel and Church House hotel, completed in 1997. Held both in person and online, the service was held in Amistad Chapel, which has served as sacred gathering space for 25 years. I heard and read the many comments from all over the world in testimony to the Chapel’s impact on people’s lives.

More than 330 employees once worked in the nine-story structure. But over the years, the staff got smaller. The UCC put 700 Prospect up for sale last fall and will be moving to one floor of leased space in May.

“Leaving 700 Prospect means leaving behind the space we have come to know and love. It’s a sacred space. A gathering place. A vessel of God’s love, of worship and extravagant welcome,” said the Rev. Karen Georgia Thompson, associate general minister.

“700 Prospect, with its Amistad Chapel, stands in a wide circle of spaces across generations that have been places of regeneration, learning, community, and healing,” said the Rev. Robert “Rip” Noble.

A Brief History

For fifteen years starting in 1994, I traveled with a group of architects associated with the UCC to study the history and design of sacred architecture. Dr. John Wesley Cook – who at the time was establishing a program of sacred art, architecture, and music at the Yale University Divinity School – became our mentor as we explored the qualities that make a sacred space.

Consequently, we were asked by the UCC to conceptualize a design for “Church House” at its Cleveland headquarters. Bob Wandel, Ann Vivian, Doug Viehmann, and Val Schute were UCC-affiliated architects who worked closely with me on the early concepts. The project comprised a new hotel and meeting house addition, and a chapel in a renovated portion of the historic building. The chapel would be named “Amistad Chapel” to commemorate the Amistad rebellion of 1839 when captives from Sierra Leone in Africa aboard the Spanish schooner “La Amistad” mutinied against human traffickers and were aided in their freedom fight by ancestors of today’s UCC.

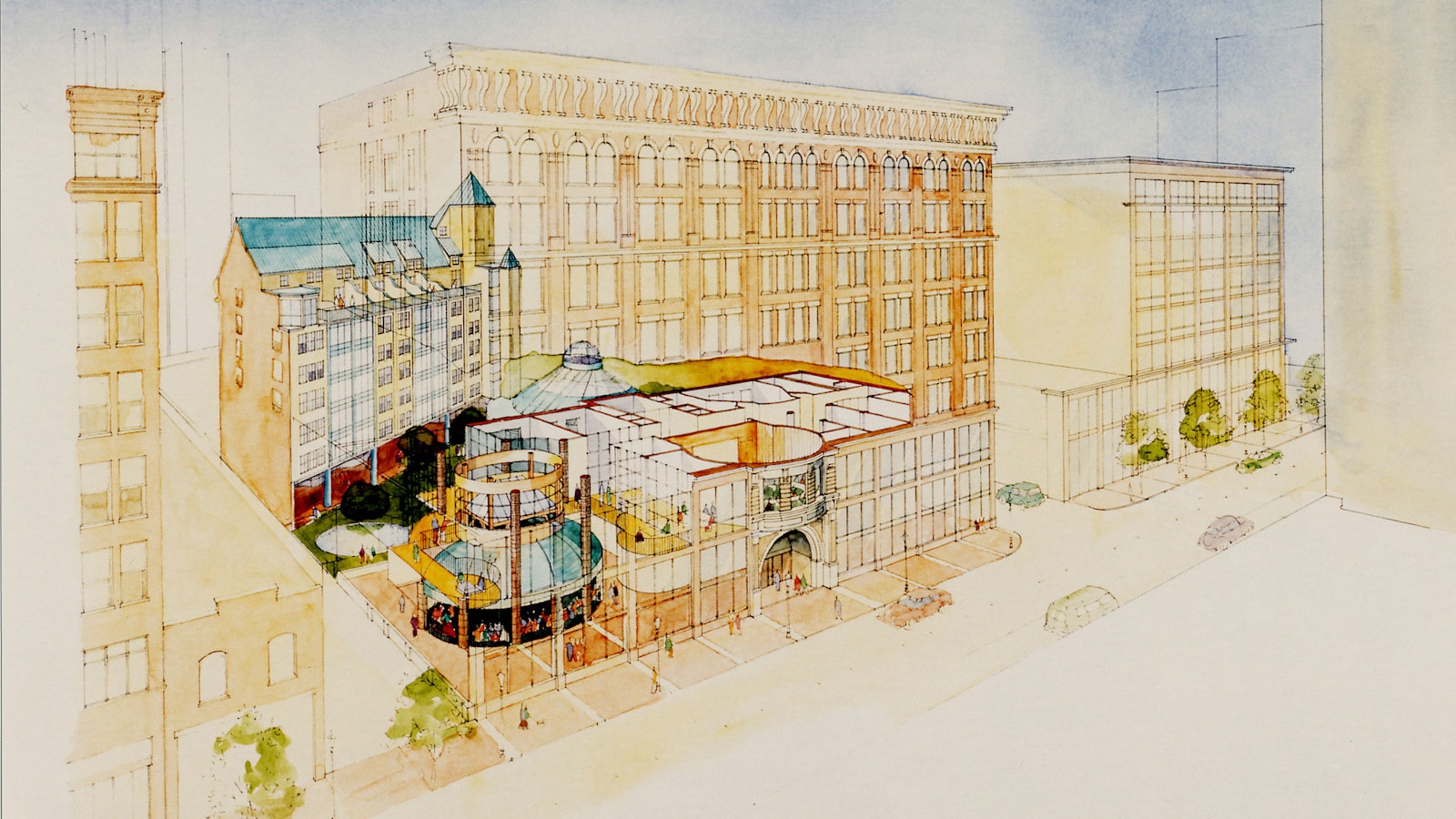

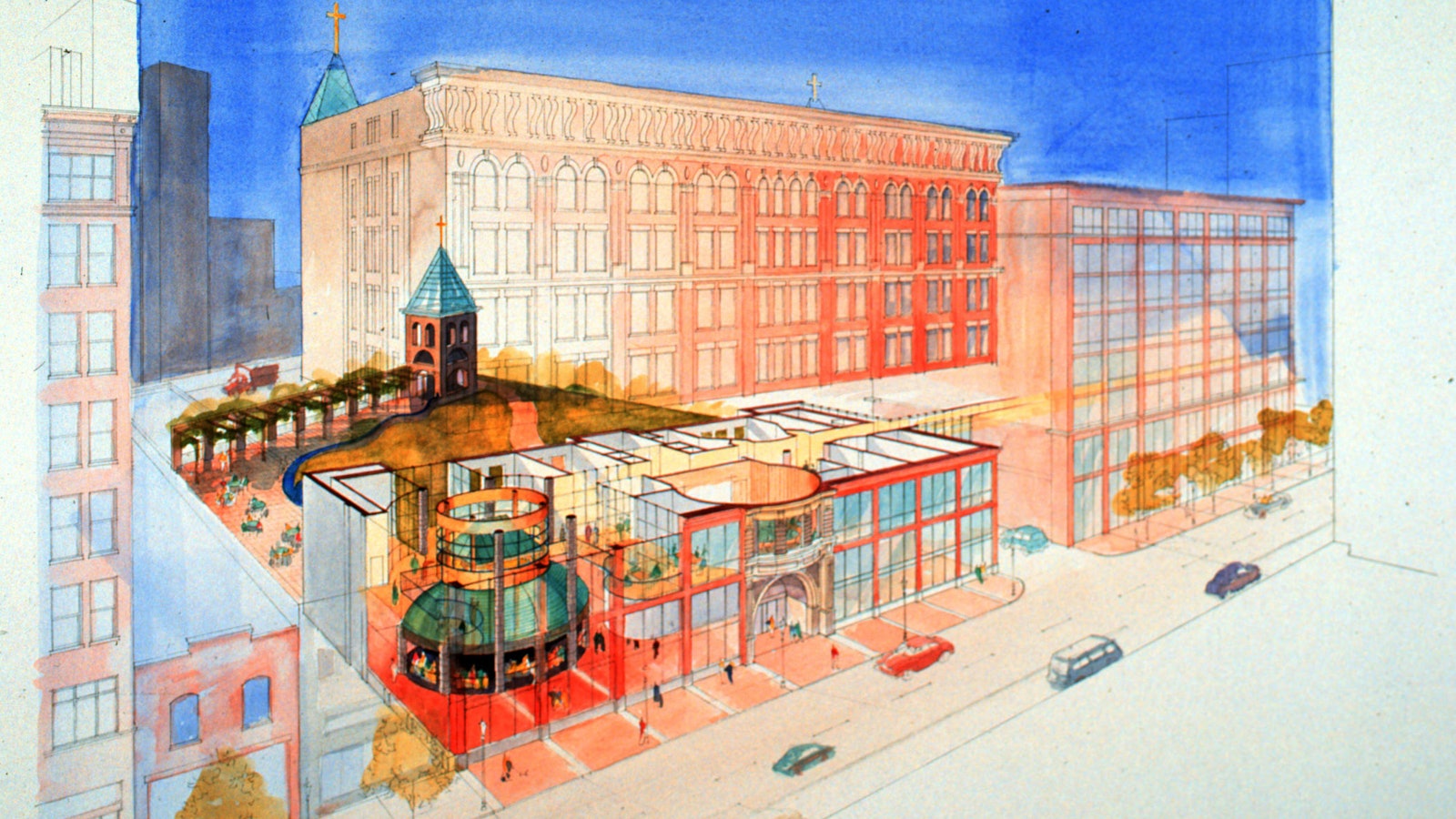

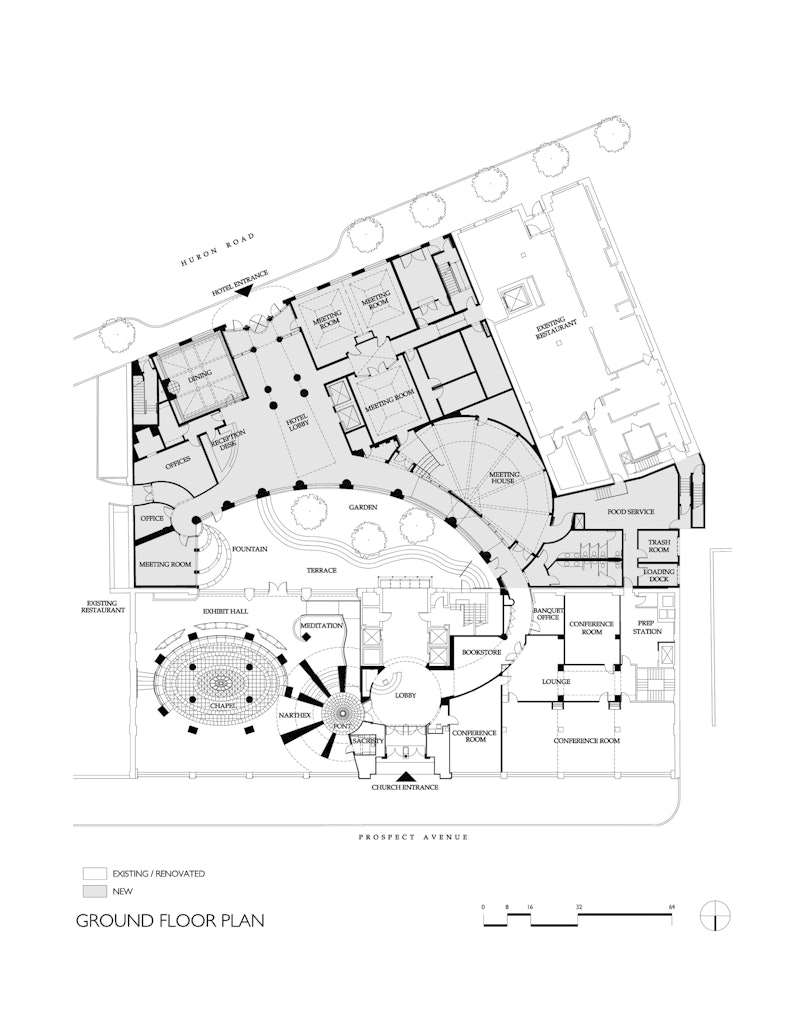

After we conceptualized options for Church House, it fell to me and my team at Centerbrook Architects to develop the design for both the hotel and chapel. The hotel was placed on a vacant lot abutting the historic building and fronting Huron Road. The chapel occupied the ground floor of the historic building fronting Prospect Avenue.

The new hotel facing Huron Road

Although facing its own street, the hotel related architecturally to the historic building on Prospect Avenue to which it was connected.

Symbolism

We designed the Chapel to be seen by passersby on Prospect Avenue, as well as from the Church House garden court. This symbolized the “priesthood of all people." It was not designed to be a cloister, but rather an open gesture of welcome. One could also see in it the role of the courtroom spectators in the Amistad story.

We created a strong organizing path from the hotel lobby past the Garden Court and Meeting House to the Narthex with its baptismal font and, finally, into the sacred space of Amistad Chapel. The path is a preparation full of anticipation.

Modeled after Sir Christopher Wren’s small chapel in London, St Stephen Walbrook (below), Amistad Chapel has seating in a non-hierarchical circular arrangement to support the belief that the priesthood belongs to all worshippers.

The Church House is a hotel to welcome travelers from around the world to the UCC Headquarters, much like the early Christian church houses in Rome. Mid-way through the design we connected to an abutting, pre-existing building, which we transformed into more hotel rooms.

“And a river went out of Eden to water the garden.” Genesis 2:10

The Garden Court connects the “Church House” to Amistad Chapel with a three-tier fountain (above) signifying the Holy Trinity. The waterfalls also signify the “river of the water of life," a place to gather in cheerfulness and prosperity. The spire, which brings daylight into the central Meeting House (above) recalls New England Congregational meeting houses.

We thought it was important to have a “prelude” to the sanctuary that would prepare you for worship. So, we created a threshold to have the emotional impact of leaving the secular world behind as you entered a sacred place. We used a baptismal font with soothing running water to set the stage and narrowed the space around it to contrast with the sanctuary’s expansive space.

I worked with York Butler, a craftsman in Connecticut, to figure out the workings of the baptismal font, which has its own symbols. It is ringed by eight gold-leafed lotus petals that spill water into the basin, the number eight in the Bible representing the new beginning when Man is resurrected into eternal life. Gold symbolizes purity, which Native Americans believed were the tears of the sun.

The act of baptism radiates to the chapel straight ahead, but also to both the world outside to the left and a place for individual meditation to the right. The Jerusalem stone floor is set in natural shapes and integrated patterns that contrast with the angular stone shapes in the sanctuary.

In the sanctuary, a glass “crown of thorns” overhead, crafted by Architectural Glass Art in Kentucky, recalls Christ’s sorrow. The light of Christ spreads by dichroic glass prisms and illuminates a glass-topped communion table, divided into 12 sections recalling Christ’s disciples. Twelve legs support the table on which the Bible and the Eucharist are laid. The light then shines through the table onto a broken world symbolized by fragments of Jerusalem stone in the floor and throughout the chapel signifying love of all people.

All this bears record of Christ’s sacrifice and His words’ victory over death. One can see this message as the spark of self-emancipation that led the Africans on the Amistad, and those who supported them in the courts, to years of confronting oppressive power structures.

The cross, at once stationary and processional, is edged with the dichroic glass prisms that spread a rainbow light in all directions.

All the wood used in the Chapel is Iroko wood harvested from Sierra Leone. Originally, I imagined the large columns clad in faceted mirrors (left) as I thought the outside world passing by would be alluringly reflected into the Chapel and give testimony to the “priesthood of all people”. It was, however, a desire quickly and decisively met by the unconvinced UCC Executive Director, Tom Dipko, who insisted on wood. We battled. Tom won. Tom was right.

The use of the ceiling as a place for conveying messages, unhindered by commerce, recalls sacred architecture throughout the world. Image courtesy of Gladskikh Tatiana/Shutterstock.

Architecture2000/Alamy

Alternative Interpretations of the Symbols

I was pleasantly reminded during the service that our intended meaning of the various symbols is not their only interpretation. I was quite captivated by the UCC’s Michael Readinger’s own interpretation of the Chapel’s symbolism. He sees the table as resembling a ship’s steering wheel; the tile floor as being like ocean waves; the font with its running water setting a nautical scene; the lights in the ceiling as stars by which the Africans navigated after their mutiny; the shards of glass as symbols of the weapons, clubs, and knives used as instruments of freedom; the tight spaces between the ceiling’s glass panels as suggesting the very tight living conditions on board the ship; the overall shape of the chapel as making it very clear you are in the hull of a ship. All of these are wonderful and welcome.

Individual interpretations are something for which we architects are forever grateful. It is a gift when the users of our buildings find personal meaning beyond what we gave them. Architecture, like a ballet, should always be, at once, a defining story and a deeply moving poem in which individuals find their own meaning.

We're using cookies to deliver you the best user experience. Learn More