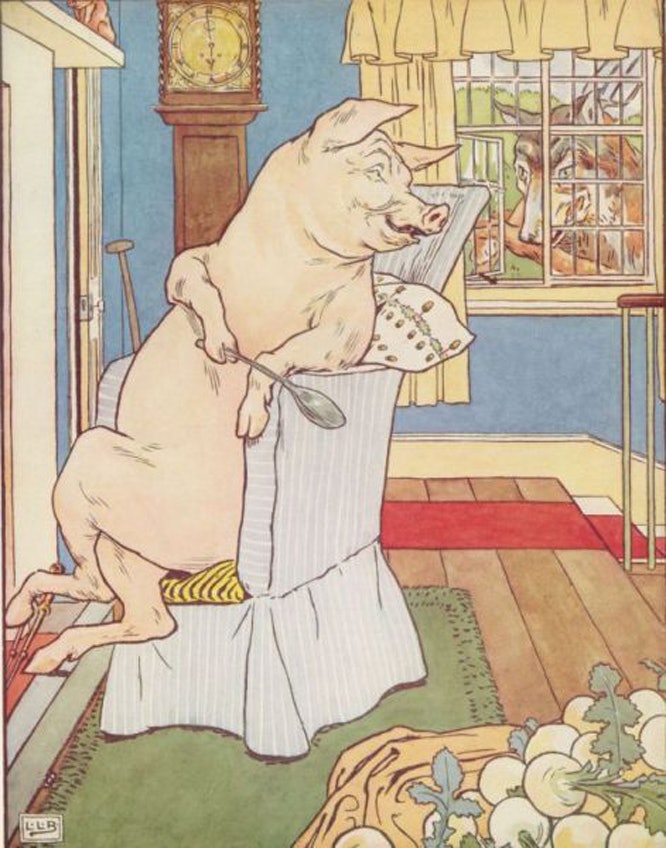

The Three Little Pigs and Sustainability

Those of us not raised by wolves know the fairy tale about the Three Little Pigs: one built a house out of straw (cheap and superficially sustainable with local, organic, and recyclable material); the second out of sticks (ditto); and the third out of bricks – a more energy intensive, durable and expensive material, but well worth it, at least in this porcine application.

In the story, the Big Bad Wolf is the arbiter of sustainability. Two of the houses, of course, were designed and built dead wrong. The moral is clear: Being sustainable, as Two Little Pigs found out, isn’t as easy as one might think.

Most of us want to do what’s right for ourselves, our clients, and the planet, but good intensions are not good enough. Pitfalls abound. As head of Product Resources at Centerbrook and charged with researching and proposing green building products for diverse projects, I appreciate how complex and variable this worthy effort can be.

Working with design teams, I seek out materials that boast a variety of potentially “green” attributes, for example: rapidly-renewable, fast-growing wood, such as bamboo or cork (the latter is cyclically harvested bark from century-old trees); or materials that embody the greatest percentages of recycled content and are regionally or locally sourced, high-performing, and low maintenance. In addition to carefully evaluating the manufacturers’ labels, certification status, and ratings, we consult with people who have used the prospective products, both in-house and beyond.

Sustainable truths are not always self-evident. “Embodied energy” is a big consideration, i.e. how much carbon is consumed to create and deliver an otherwise desirable product: in the extraction of raw materials, fabrication, and transportation? For example, we take into account what is involved in getting that renewable bamboo from Asia, and cork from Portugal, to the construction site. We determine if a potential wood product is FSC (Forest Stewardship Council) certified, i.e. was it cut from woodlands that are managed to sustain both forest growth and the ongoing timber harvest? Other options are reclaimed lumber or boards fashioned from naturally damaged or felled trees.

Sustainable truths are not always self-evident. “Embodied energy” is a big consideration, i.e. how much carbon is consumed to create and deliver an otherwise desirable product: in the extraction of raw materials, fabrication, and transportation? For example, we take into account what is involved in getting that renewable bamboo from Asia, and cork from Portugal, to the construction site. We determine if a potential wood product is FSC (Forest Stewardship Council) certified, i.e. was it cut from woodlands that are managed to sustain both forest growth and the ongoing timber harvest? Other options are reclaimed lumber or boards fashioned from naturally damaged or felled trees.

Opting for veneer instead of whole lumber is another way to save on wood consumption. Without compromising finished appearance, a single tree used for ultra-fine veneer can leave hundreds more standing. Engineered plywood and laminated boards can out-perform whole lumber in inherent strength and durability, while consuming less virgin timber. Man-made materials such as fiberglass, vinyl, and PVCs also have favorable maintenance and durability features, although we have to be mindful of trade-offs inherent in their manufacture and chemical makeup.

Green considerations extend, too, into the interiors of buildings. We examine the paints for the walls and trim as well as the carpets and their adhesives to ensure they are low in VOCs (Volatile Organic Compounds), which can affect indoor air quality. There are options now that involve minimal use of toxic compounds, which can be dangerous to the people who produce them or live close to where they are manufactured.

We look to see if a product is rated C2C (Cradle to Cradle), meaning is it durable and engineered to have a second use beyond its first life – can it be recycled or “down-cycled” into another useful form, never to be deposited directly into a land-fill or the incinerator? In a similar vein, agricultural byproducts from wheat, rice, cottonseed, soy, and sorghum have been used historically in construction and are being deployed again, for example, as the core components for SIPs (structurally insulated panels).

The tricky part to this brave new green world – with all the products in it – is that every project is unique. Wind turbines and solar panels are not for everyone or everywhere. Their greenness is affected by variables that can be quite subtle. To see if a given product or approach makes sense for a specific building, we look to life-cycle analysis data – typically tabulated via computer program – and calculate ROI (Return on Investment). The two arrays of solar panels on our own office roofs, for example, will pay for themselves in less than ten years.

With so many options and products, sustainable design is not a straight line through the buffet, ladling one of everything onto the plate. The path is more like a pig’s squiggly tail. Pieces and systems have to be compatible, fit within a budget, and contribute to (or at lease not sabotage) the design aesthetic. Unlike fairy tales, which tend to be black and white, the real world is populated by large swaths of gray.

With so many options and products, sustainable design is not a straight line through the buffet, ladling one of everything onto the plate. The path is more like a pig’s squiggly tail. Pieces and systems have to be compatible, fit within a budget, and contribute to (or at lease not sabotage) the design aesthetic. Unlike fairy tales, which tend to be black and white, the real world is populated by large swaths of gray.

But remaining responsibly aware of sustainable principles and options will make for happier endings, for us, our clients, and for the planet. They can help to keep the wolf from the door.

We're using cookies to deliver you the best user experience. Learn More